First published In June 2013, in the Write4Children journal, this paper considers e-book accessibility and literacy norms in relation to dyslexia. Beginning with a personal account of e-book accessibility, the technical and corporate challenges of accessible publishing are briefly reflected upon. The production of ‘dyslexia’ is then explored in terms of Craig Collinson’s (2012) ‘lexism’, which relocates the problem of dyslexia as not individually owned, but rather the consequence of expressing diverse reading, writing, speaking and hearing in relation to ‘literacy norms’. This considers how dyslexics defy language conventions and thus are able to facilitate alternative knowledge interpretations of the world. In this way it is suggested that while accessible e-books have the potential to liberate readers in progressive ways, this can only be achieved if every-day and institutional language producers resist the literacy norms through which we are socially ordered to perform speech acts in particular ways. Sally Gardner’s recent book, Maggot Moon, is then considered for the way in which it promotes a positive representation of dyslexia and the leadership the book shows by way of it’s multi format and accessible publishing style.

Introduction

Along with the incorporation of computer and internet technology into our everyday lives has come also the enabling potential of accessible reading devices. This is not only in terms of enriching literature and liberatory knowledge tomes previously locked away in the elite and dusty corridors of learning institutions, but also the manner in which such material can be viewed, understood and experienced. Technology is very much a tool for inclusion that embraces, rather than rejects human diversity. The development of hard/softwares has given people, in some circles termed ‘print disabilities’, who read in diverse ways, such as through screen text readers, colour contrasting filters using highlighted text displays, and or a combination of each some access to literature that many take for granted. This can be claimed as progress, and has begun the enablement and repositioning of the ‘illiterate’, to that of those ‘oppressed’ by dominant literacy norms, and who can be freed by facilitative reading technologies. Furthermore, accessible reading devices make the physical act of turning pages easier, useful for those experiencing coordination or physical impairments. There are significant benefits for all of us by way of a computer and internet technology that enables new ways to engage in the reading experience.

E-book accessibility

E-book technology has enabled much greater access to literature for disabled readers and initiatives, such as Bookshare.org with over 64,000 books for readers with ‘print disabilities’ mean the availability of literature continues to grow. Personally, such developments have meant that I as ‘dyslexic’, having been thrown out of school, and never reading a book until in my twenties have been enabled to read extensively, complete a degree, masters and PhD. However, there is still some way to go to achieve fully accessible reading options that are equal to those that don’t require assistive reading technology. Indeed copyright restrictions and the exclusionary practises of some publishers mean that while masses of reading material could be made available to those that use reading technologies, it is not because of the fear of profit loss of large scale email distribution if it they are made available in text only formats. With that said there are some excellent examples of work to address such issues, including librivox (http://librivox.org/), a volunteer led free audio book initiative seeking to put all out of copyright books in audio. As a result the works of Marx, Freud, Keller and many others are now known and enjoyed by me.

Despite my enthusiasm for the electronic e-book, I’m well aware of its limits. Crucially the digital divide currently segregates huge numbers, and is exacerbated by the excitement to do everything, from public services to dating, online. This is without consideration it seems for the very real fact that some people don’t actually have a computer and might not ever get access to one for material and other reasons of compatibility. Additionally, there remain very prominent technological limitations. For example, recently I’ve undertaken some teaching in a higher education setting and in preparing the materials was given access to the main textbook both in hard and online copy. The hard copy is so heavy and bulky turning and keeping the pages open was a nightmare fit for my coordination and clumsiness. The online e-book version, while available online, should not have been really considered an e-book I feel, as it was merely a collection of images, one for each page, rendering it completely inaccessible to a screen reader or end user manipulation. This raises the question as to whether the higher education institution should be using this text as it presumably breaches the Equality Act in some way. Indeed, in the US several universities recently signed an agreement with the Justice department to not purchase, recommend or promote any e-readers that are not fully accessible (see Higginbottom 2010).

This e-inaccessibility extends also to academic journals. While often made available in electronic PDF versions, these are with great variability in terms of accessibility for those using reading technologies. While I can manage to get some to work to an ok standard, when outputting the seemingly ‘accessible’ PDFs to my screen reader, so that I can have the text read out loud, additional information in the document like the headers and footers often blurts itself onto my accessible page style. The following is from a recent article I read, which I call ‘footer intrusion’;

As Rice (2005)pointed out, there is a tendency within some specialbs_bs_banner RETHINKING DYSLEXIA © 2012 The Author. British Journal of Special Education © 2012 NA SEN. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2012.00538.educational needs textbooks designed for teachers to see ‘inclusive education…as an “add-on”.

This mid sentence entry of irrelevant text disrupts reading flow. Other hiccups when outputting to my screen reader can include what I call ‘no spacers’;

‘Paranoia:asocialaccountIntroductionParanoiacanbedefinedasawayofperceivingandrelatingotherpeopleandtotheworldthatischaracterizedbysomedegreeofsuspicion,mistrust,orhostility’.

Or ‘extra spacers’;

‘T h e t e r m n a r r a t I v e I d e n t I t y r e f e r s t o t h e p e r s o n a l e v o l v I n g s t o r y o f t h e s e l f t h a t a n I n d I v I d u a l c o n s c I o u s l y a n d u n c o n s c I o u s l y c r e a t e s t o b I n d t o g e t h e r m a n y d I f f e r e n t a s p e c t s o f t h e s e l f’

All of which make the conversion of text to speech difficult and unmanageable. There are many other examples too, all of which can add disruption to more or less an extent to reading, which can in turn impact on learning. This however would be overcome by making available the text in, quite simply a text only format. However, the dominance of copyright conventions prevent this unfortunately, despite the numerous benefits for doing so.

With this in mind, what then does a fully accessible e-book and text look like? My view is that it is something produced in multiple formats that are adaptive and reflective. Bearing in mind authorship ultimately creative, ensuring multiple format production would help engage diverse readers in ways that connect with their perceptual styles. Ultimately this would require the availability of raw text so that those with reading technologies can manipulate its output to suit them. Furthermore, ensuring a reflective approach, that is never producing the final version, rather accepting reader feedback and reproducing the material so as to enhance its presentation inclusively. While both technological and legal improvements would help develop e-book accessibility, there are also cultural and historical issues of ‘literacy norms’ that perpetuate traditional ways of producing reading materials which we will now consider.

Resisting literacy norms

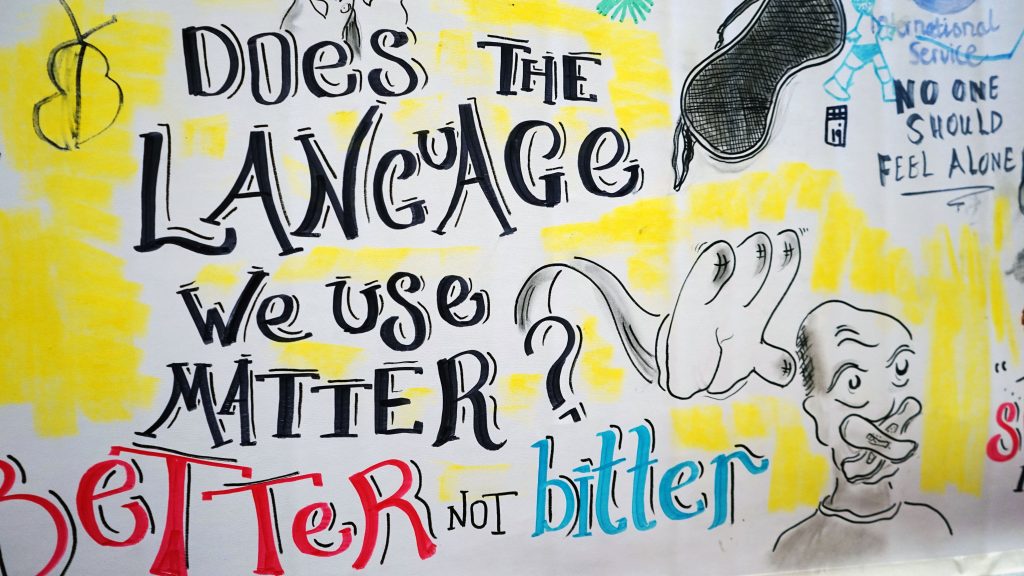

No matter how far e-accessibility or assistive reading technologies advance, reading liberation will remain constrained unless our literacy norms are reconsidered and reworked. The way we speak and write, and the associated tendencies and assumption are embedded within a historical and cultural context. Craig Collinson (2012) asserts ‘lexism’ as the problem for dyslexics in the way it enables the sustainability of ‘literacy norms’. Lexism is articulated as ‘the normative practices and assumptions of literacy’ established through historical and institutional knowledge practices, such as rigid grammatical standardisation and the identification, and invention of language use ‘deficits’ by psycho-educational professions (Collinson 2012). Lexism is the social practise that creates dyslexia as dysfunction, through the way it projects and upholds a singular version of correct language use. Literacy norms then become regulatory and oppressive practises for all language users in the way they deny the lived experiences of diverse readers, writers, speakers and hearers who process and express textual information in very complex, variable and creative ways. Literacy norms therefore deny the inevitable realities of alternative reading styles.

The work of Michel Foucault (1926 – 1984) is also significant to dsylexia. He produced a number of works including The Birth of the Clinic (1963) and Madness and Civilisation (1961) that give a history of the development of structural conditions that made visible and oppressed the ‘abnormal’ body and mind. Central to the work of Foucault is the relationship between power, knowledge and discourse and the drive to question everything, particularly that which is considered natural and inevitable.

For Foucault, power is a productive and shared resource, operating across the realm of social life, ever persistent in the transmission of knowledge forms and regimes of truth. Foucault asserted that human life is subject to disciplinary power that produces and regulates desired behaviours. Such as the construction of psychiatry and the establishment of the asylum (Foucault, 1961) and literacy norms that specify ways of speaking, writing, reading and listening, and reject diversity within it.

Recent research by Tom Campbell drawing on the work of Foucault explores the creation of dyslexia through excessive educational professionalism and standardisation of language conduct. The development of categories to describe language dysfunction such as ‘word blindness’ emerge during the nineteenth century as medicine becomes concerned with reading difficulties. As part of a broader project concerned with developing a genealogy of dyslexia Campbell (2011) considers how clinical criteria’s concerning congenital word-blindness were negotiated in relation to ideological strategies of government working to capitalise the population.

For Foucault power/knowledge are expressed through discourse (Foucault 1972). Discourse, is a system of representation and signifiers, where rules and practices apply to set the tone and detail of what, and how topics and concepts can be constructed. This includes the text and spoken words, but also other signs, forms and mediums of expression, such as the body, or a map. Discourse provides a way of speaking and knowing things through language. Statements or concepts of certain knowledge objects, such as dyslexia that drift towards, or support common institutional strategies or ideological patterns are drawn from shared repertoires and discursive formations. It is discourse that produces objects of knowledge, does so it certain ways, without which meaning about them can not exist. This does not deny our realities of, say dyslexia but rather reminds us that they are versions of it, variable, influenced and related to actions in previous times, spaces and structures. Bad grammar and the production of text in alternative unconventional ways is challenging not because it is something we are not use to doing, but as it disrupts the a social, cultural and historical power that seeks order through language conformity.

Dyslexics defy language conventions, not by way of neurological deficits, but rather by an inability to accept and main standard rules and thus facilitate alternative interpretations of the world. In this way while accessible ebooks have the potential to liberate readers in progressive ways, this project will be flawed if it chooses to constrain itself by uncritically accepting and upholding literacy norms through which we have been socially ordered. Yet all is not lost, there is leadership, as we can see through the creative presentation and multi format publishing of ‘Maggot Moon’.

On Maggot Moon

Maggot Moon is very good example of inclusive publishing. As well as giving an insider account of the experience of dyslexia, it is a stimulating read with a very visual storyline. It is both imaginative and inspirational, and gives space for the reader to really absorb what’s going on and add in extra detail as it is read. Despite the oppressively dark and sinister backdrop, the central character ‘Standish’ beams a very bright light from every page. It is a tale of proud resistance set in a fascist state where, in the end, the power of what’s right rings true.

Like both the author Sally Gardner and I, ‘Standish’ is dyslexic, although this is not explicitly labelled in the text, rather this is implied in the opening pages with the line, ‘Can’t read, can’t write, Standish Treadwell isn’t bright’. However the text does not locate this as a deficit belonging to ‘Standish’, but quite smartly highlights the unique quality of his diversity and the problem as theirs; that is the traditional attitudes of others, the school system and society. This is reflected in the style and presentation of language that often creatively reworks typical linguist conventions, emphasising the visualise of the world as seen by the neurodiverse, that is as Standish states ‘eye-bending in its beauty’.

Sally Gardner has done a good job of promoting dyslexic pride with this work and while this is positive I am left slightly confused by a quote on the website related to the book that asserts dyslexia as being not a disability, but a gift. Even though I understand this perspective, I would challenge this in terms of the social model of disability, in which people are disabled by barriers in society and not by the diversity of their bodies or minds, that is peoples impairments or conditions. While dyslexia is not a deficit, society does disabled dyslexics through the way it rejects and ridicules our unique and beautiful thinking and communication style that challenges and does not conform to the traditions of an outdated and exclusionary education system. For dyslexics to disassociate with the politics of disability, the collective struggle of disabled people, and other marginalised identities, to achieve an inclusive and equal world is weakened. By sharing the similarities of our struggle, we will be able to be stronger in our demands for inclusion.

As well as being a gripping story this book is really exceptional in terms of showing some publishing leadership in terms of both accessible communication and inclusive design. I love books but the act of reading is hard work, my preference being to have the text spoken by a screen reader, or to use a see through colour sheet to minimise the glare and movement of the characters. So although I can read printed books this is a challenge as the words bounce around the page and my mind easily wanders off. I often find myself flicking ahead and thinking ‘OMG – shiny moving pages making no sense at all, how many pages left in this chapter, how many, AHHH I cant cope’ and throw the book at the wall. Maggot Moon has one hundred chapters, but each one is no more than a couple of pages and is subtly illustrated with a mute flicker book style. This, and the low contrast cream colour pages made this very easy for me to maintain my attention. Additionally, the book is available in audio, and as an ibook that has loads of additional content that makes it not just a read but a super story experience. Through this Maggot Moon challenges publishing convention through its multi publishing formats and thus by doing so literacy norms. This is particularly emphasised by the grammatical creativity of the text and the fact that it validates and legitimises diverse readers, writers, speakers, hearers, as Craig Collinson (2012) would suggest those that are cast into shadow by ‘lexism’ and ‘literacy norms’ that sustain a dyslexic discourse of language dysfunction, not diversity.

Conclusion

While e-books have revolutionised access to reading material for those previously excluded from it, inclusion in this area is yet to be fully achieved. Not only are there socio legal and technical challenges, but also historical and cultural legacies and assumptions, that is ‘literacy norms’ that dominate our perspective on what constitutes acceptable speaking, writing, hearing and reading. Sally Gardener’s ‘Maggot Moon’ however shows that such literacy norms can be reworked, which in turn enables a re-narration of dyslexia, told by those labelled negatively in such ways. From this then alternative ways of language use can come to life and be possibly used to challenge restrictive and traditional ways of only ever doing certain things in certain ways, and allow a wider range of the diverse lived experience to be known and included.

References

Campbell, T. (2011). ‘From aphasia to dyslexia, a fragment of a genealogy: An analysis of the formation of a ‘medical diagnosis’. Health Sociology Review: Volume 20, Issue 4.

Collingson, C. (2012). Dyslexics in time machines and alternate realities: thought experiments on the existence of dyslexics, `dyslexia’ and `Lexism’. British Journal of Special Education, Volume 39, Number 2, p. 63-70(8).

Foucault, M. (1961). Madness and Civilization. Routledge, London.

Foucault, M. (1963). The Birth of the Clinic. Routledge, London.

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon.

Gardener, S. (2013). Maggot Moon. Hot Key Books.

Higginbottom, A. (2010) The tale of the accessible eBook. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ouch/features/ebook_readers.shtml Accessed March 2013